Source: AT THE CIRCUS Practice Book Series by Rod Everhart, WJU#1351

The American circus is a unique form of entertainment that has been a key part of U.S. culture for over 200 years. Traditional circus music evolved as a key element of those circus performances.

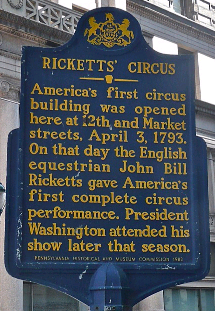

While he was serving as our first president, George Washington attended the John Bill Ricketts Circus in Philadelphia in 1793. Ricketts was an excellent equestrian and his circus included mostly feats of horsemanship, plus some rope-dancing, tumbling and comedic acrobatics thrown in.

Back then, the facility, built specifically for the circus, was a four-walled, wooden, roofless arena with about 800 seats surrounding a circular riding space 42 feet in diameter. Circuses were in temporary wooden structures until 1825 when Joshua Purdy Brown went on the road with the first circus tent. Over time, the tents got larger and larger, with Ringling’s eventually big enough to hold 10,000 to 12,000 people. Hence the circus term for the main tent: “The Big Top”.

The circus made its first appearance in America around 1792. In its early form, the circus was comprised of various animal displays and some modest acrobatic performances. As these proved popular with the American people, circus entrepreneurs launched increasingly complex enterprises to take advantage of this new opportunity to generate earnings, and in many cases, substantial wealth. The American circus then evolved its own unique approach, atmosphere, and excitement, unlike its European heritage.

The circus was particularly popular during the 100 years between 1850 and 1950, with famous names like Barnum & Bailey’s “Greatest Show on Earth” Circus and Ringling Brothers Circus … and hundreds of less-famous names like Gollmar Brothers, Sells-Floto Shows, Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus, Gentry Brothers Dog and Pony Show, Robinson Circus, and the Nickel Plate Circus.

A special boost occurred following the Civil War when war-weary citizens were enthusiastically ready to be entertained again. The touring circus caught their imaginations and they quickly embraced the excitement of the traveling circus, the sideshows and menageries, and all of the associated hyperbole.

The ability to move large circuses via the railroad versus horse-drawn wagons was a significant factor in the growth of these shows to rural areas of the country, where “big city” entertainment was not available. The first railroad circus cars were built for the Barnum Circus in 1872. P.T. Barnum (1810 – 1891) was a visionary in that regard, with his early adoption of this new transportation methodology to take his New York-based museum and show on the road.

As the popularity of circuses expanded, so did the variety and daring of the acts presented. The advent of the three-ring circus, with its multiple simultaneous performances, created still more excitement, and made the circus even more spectacular.

But World War I, the Depression, and World War II delivered successive blows to the circus industry in the first half of the Twentieth Century, as audiences focused on the country’s critical issues. The introduction of radio and touring “Big Bands” and orchestras as alternative entertainment sources further diluted the circus’s ability to draw large audiences.

While the American circus still exists, there are fewer of them and many perform exclusively in convention centers across the nation. With rare exceptions, the Big Tops and associated “tent cities” have gone by the wayside. With that, the use of “traditional” circus music has also largely faded, often replaced by recorded “popular” music. Nevertheless, music still plays a critical role in adding to the excitement.